Working and the information problem

August 19, 2012

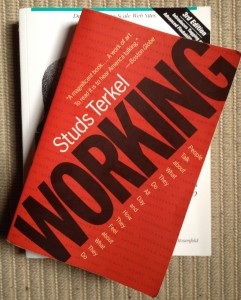

_Working_ is an oral history of work in 1960s and 70s America. Historian Studs Terkel interviews a vast range of different people - bookbinders, parking lot attendants, CEOs, retired people, musicians, and many others. In today’s world, and especially in the world I inhabit where I spend almost all my time talking to software engineers, marketers, and salespeople, it’s fascinating to read about what it’s really like to be a garbageman or a baseball player.

There’s a huge amount I could write about this book; its honest picture of labor and race relations in 1960s America, by itself, is striking, as are the various characters’ reflections on what it means to work and why. But I actually wanted to write about something more boring, which is the information problem. This book will make you acutely aware of it.

What I mean by the information problem is: as good as we’ve gotten at building global communications networks and developing common languages for subjects, we’re still actually not very good at giving basic information to each other. For example, I was telling one of my best friends (an academic) about the interview process at the company where I work. When I told him I had had eight interviews, he almost fell over. In his experience, an “interview” takes all day, and requires you to talk in great depth about a very specific area with people who may know much more than you do. But of course in business an interview may take an hour or less and is as much memorization as it is intensive preparation and thought.

How is it that we had such wildly different assumptions? Partly, I think it’s because we are often so immersed in our context that the important details are ones we fail to notice, fail to realize are important, or are perhaps even completely unaware of. This creates lots of problems in a software company:

When a user files a bug report, they don’t know what information to include, or may not include any information (“site is broken”)

When an engineer builds a system, they don’t explain (and I forget to ask about) some critical information about the way it is built, which ends up creating problems or miscommunications later

Customers are unable to articulate what they really want, so I have to test lots of different designs and product prototypes before they’ll buy

I build a user interface that I like, but nobody else understands how to use it

I write code that doesn’t scale, because I’ve never had to deal with scale before

It should be pretty easy to come up with examples of this happening in other companies, in your life, in the world, etc.

We’ve developed solutions to the information problem, or, as Don Norman refers to it in The Design of Everyday Things, the problem of getting information out of your head and into the world. These solutions mostly include very thoughtful specifying, testing and prototyping. I write detailed technical specifications that can then be discussed and tested against many people’s assumptions. I do A/B testing on my site to see how people actually act when they see a new user interface or marketing pitch. I build simple prototypes to see whether a product or service I want to provide, or code for that matter, actually works.

Anyway, Terkel’s book will make you highly aware of these problems, and how little you know about the problems other people face, especially as you get further and further away from your area of expertise. Here are some problems that garbagemen have:

In some neighborhoods, kids yell at, and taunt you (“they’re too stupid to realize the necessity of the job”)

Once in a while, people often throw away extremely heavy (plaster) or dangerous (acid) materials

The compression mechanism at the back of a truck can sometimes cause things to shoot out

And stonemasons:

When building a fireplace, it’s possible to reflect varying degrees of heat back into the house depending on the design

Stones (even of the same type) will break and split different ways, sometimes unpredictably

Having a good hod carrier (who carries building materials and makes mortar) is critical for productivity

This is a tiny sample of the obscure bits of the information I never even considered, that have come up in reading this book. It reinforces to me (a) how difficult it is to really understand someone else, i.e. a potential customer, when that customer isn’t you, and (b) how many problems there are to solve, and perhaps solve very profitably, that I likely have no way of learning about.

(And this is only, of course, restricting my thought to the mechanics of a job or task, never mind the far more complex and arguably more important understanding of how other people live their lives.)