Understanding flour

September 26, 2010

A few years ago, I heard Alton Brown make a comment that has stuck in my head ever since. “A starch high in amylopectin,” he said, “will not create a gel that is quite as thick as amylose, but it will tolerate temperatures well below freezing. So, for my frozen pie filling, I will go with amylopectin-packed tapioca flour.”

First of all, let me say that I am aware that this is not the type of comment that sticks in normal people’s heads.

But having said that, this was so surprising to me because I had no idea flour could do this for you. And yet here Alton Brown was, casually using an obscure flour for an obscure, but probably good, reason. I have no idea whether this substitution is actually effective. But it made me wonder, can I one day improve my recipes by thinking creatively about flour? As a first step, I’ve written this entry.

First of all, what is flour?

Generally, flour is any powder made out of grains, or sometimes seeds or roots, or indeed nuts (e.g. almond flour). You can also make flour from things like crickets, and yes, make cricket bread.

Etymologically, the word “flour” has the same root as “flower”. Both come from the French fleur, which refers to a flower. The word flour originated in the phrase fleur de farine, “the flower of the meal”, i.e. the finest part of the meal, since flour is a refined grain.

You may have encountered this idiom yourself if you’ve bought any fleur de sel, “the flower of the salt”, i.e. the best salt you can buy.

Flour appears to have two main components, starch and protein (gluten).

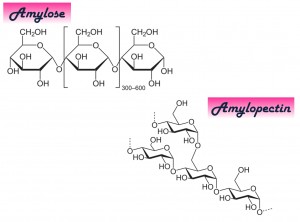

The starch consists largely of two long sugar molecules, amylose and amylopectin.

Amylopectin is a branched molecule. When you add water to it, it readily takes up the water molecules and forms a sticky gel.

Amylose, on the other hand, has linear chains which are harder to break and which therefore don’t gelatinize as easily.

This ratio helps to explain why different types of rice behave differently. Rice that is high in amylopectin content, such as short and medium grain rice, tends to stick – think sushi rice. Your typical supermarket rice, which is fluffy when cooked, has high amylose content.

The protein you will likely have encountered – gluten – also comprises two molecules, glutenin and gliadin.

Glutenin and gliadin both contain bonds of two sulfur molecules. Why does this matter? Because when these molecules are agitated (e.g. when you knead a dough) in the presence of water, the bonds within the glutenin molecules break and reform between molecules.

The result is a tough, elastic network that gives bread its form. The more you knead, or the more time you leave the dough to develop, the tougher it will be.

Many flours do not contain gluten. Instead, (a) they have some other protein that fulfills this function, or (b) you might need to actually add gluten or wheat flour.

There are lots of other things to talk about also, but those seem to be the main relevant components. So what are the differences between different types of flour?

Protein (gluten) content.

Bread flour has a protein content of around 13%. All-purpose flour has a protein content of about 11%, and cake flour has a protein content of 7% - 8%.

As a result, cakes tend to be fluffy and soft, bread is chewy and elastic, and most other things are somewhere in the middle.

Whole wheat vs. white flour.

Whole wheat flour contains the entire wheat grain; white flour contains only the part of the grain that the seed uses to grow.

Whole wheat flour has more nutrients, but is denser and therefore requires more leavening to rise.

Note that products that are advertised as “whole wheat” aren’t necessarily made entirely with whole wheat flour; only 51% whole wheat flour is required.

Different ratios of amylose to amylopectin.

Above, I said that amylopectin tends to gel more readily. In practice, this means that flours higher in amylopectin can be used at lower temperatures (though the gel may not be as strong).

This means that, as a crazy example, if you are making a pie with a frozen filling, you’ll want to use a high-amylopectin flour so that the crust can still come together even at a low temperature.

Lots of other things.

- For more information and detail about different flour types, check out this article. And this article gives an awesome, and much more detailed, overview of the complex molecular interactions at play.