The Four Seasons' pastry kitchen

December 27, 2010

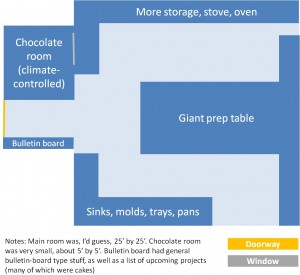

[caption id="attachment_963" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="(Very) approximate layout of the kitchen."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_963" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="(Very) approximate layout of the kitchen."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_934" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Basic ingredients."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_934" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Basic ingredients."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_935" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Piping out the mixture."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_935" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Piping out the mixture."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_936" align="alignleft" width="261" caption="Chef Hales with the final product."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_936" align="alignleft" width="261" caption="Chef Hales with the final product."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_937" align="alignleft" width="218" caption="Awesome chocolate decorations!"][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_937" align="alignleft" width="218" caption="Awesome chocolate decorations!"][/caption]

I had the chance recently to visit the pastry kitchen at the Four Seasons Philadelphia. It’s one fairly large room (I’d say 25’x25’), connected to a very small temperature-controlled room where some completed desserts and various chocolate-related ingredients were kept.

I’ve had the chance to visit a few industrial food production areas, including getting really familiar with some yogurt factories in my days as an investment banker, various public factory tours (such as the Tillamook cheese factory), and now this kitchen, which was definitely industrial-grade.

It always strikes me how a very mechanical, utilitarian place can be devoted to something decidedly non-industrial, i.e. high-quality, complex, delicious food. I guess you can tie it to my larger interest in commercialization and mass production, of which food production is a particularly interesting example because the end product gives very little evidence of how it was prepared. One particular thing I noticed during our tour was a bunch of miniature fruit tarts - the colors of the strawberries and blueberries were conspicuous against the otherwise neutral (metal, cinderblock and orange tile) surfaces.

Anyway, it was pretty neat to see the various tools that are used and how they’re arranged. In some ways it would be a dream kitchen - vast stainless steel work surfaces, and lots of trays, pans, molds etc. hanging up on the walls. When a chef would finish with a particular piece of equipment, he or she would put it into a sink full of hot, soapy water. About every half-hour, someone would come by to collect the dishes for further cleaning and tidy up, as far as I could tell.

Our guide to the kitchen was Eddie Hales, who has been doing pastry for… a long time. He first showed us the small chocolate room I mentioned. The most interesting part of this was the chocolate transfer sheets he showed us, which you can get a glimpse of in the last picture. Check out some examples of these here. These are plastic sheets on which tinted, patterned cocoa butter has been deposited. (There are lots of different patterns available, some of which seem to be quite complex.)

When you want to use one, you cover the patterned side with a thin layer of melted chocolate. You wait a bit for it to harden, and then you press the chocolate layer to whatever you want to decorate. Then you carefully pull the sheet off. The chocolate, with the pattern facing out, is left behind. You can also just let the sheet fully harden by itself, then break it up to get patterned shards. Pretty neat technology.

Chef Hales also did a pâte à choux demonstration for us. If I remember correctly, he mixed together milk, butter, flour and eggs, cooked the mixture, and put it in the stand mixer. The result was a very thick dough, which the chef piped out onto a tray, and baked. This is how you make e.g. profiteroles and some other puffy desserts, e.g. eclairs.